Skadi Loist & Zhenya Samoilova

1. Why Study Festivals?

In the last ten years, we have seen a wide expansion of the film festival market. Along with commercial cinema releases and streaming services, film festivals currently provide another exhibition window. Festivals make up a unique and for some smaller films the only exhibition network. According to the Canadian magazine The Star, 20 percent of the films shown at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in 2017 were shown only at festivals (Mudhar & Bailey, 2017). Yet, the role festivals play within global exhibition and distribution patterns has hardly been discussed within research on film distribution.

Although some festival screenings are recognized as important for reference funding, there is no empirical data on the broader festival market. At the same time, distributors of small art house films argue that festivals are skimming off cinema audiences, which forces them to compensate the lack of revenues from cinema releases by charging screening fees to festivals. In 2013, the Film Collaborative, a US non-profit film agency acting as a world sales agent for independent films, published a statistic on average revenue from the festival circuit based on films it represents on the festival circuit. Depending on premiere location, budget, genre, director, producer, genre and specialized content, such as LGBTI*Q topics, films could collect up to 87.000 US$ (The Film Collaborative, 2013). Meanwhile, smaller, specialized producers started to calculate festival revenue and include it in their production budget. The BMBF-funded research project “Film Circulation in the International Festival Network and the Influence on Global Film Culture” studies these developments by collecting and analyzing empirical data on the film movements on the festival circuit, so-called festival runs.

In the first instance, the project follows films shown at six major film festivals in festival season 2013. We are not only interested in the number of screenings in each festival run, but also in the parameters that can influence further circulation patterns in the festival circuit, such as country of production, length, budget, genre or commercial cinema exploitation in different countries. At the second level, the project looks at the festival network and examines which of the festivals act as network nodes or hubs. Further questions include: Which thematic (e.g., LGBT*Q, human rights, documentary) or regional circuits are emerging? What can be said about the hierarchical structure of the festival circuit? And how does this influence the film circulation patterns?

Until now, research on this topic has been limited to theoretical considerations (e.g., De Valck, 2007; Iordanova, 2009; Loist, 2016) or individual, qualitative case studies (e.g., Vallejo, 2015; Sun, 2015; Peirano, 2018). The fact that data are not available or not accessible in an easily usable form contributes to this research gap. In order to empirically investigate complex temporal and spatial circulation patterns within the festival circuit and ensure the quality of the data, the project draws on several data sources.

2. Combining Digital and Traditional Data Sources

New sources of digital data can help answer new research questions as well as use new approaches in answering old ones. While these new sources can help us collect data that was previously unavailable, they also pose challenges such as the necessity for interdisciplinary team work as well as the important assessment of data quality. These aspects are currently discussed in the area of the Digital Humanities (DH). For example, the work by the Kinomatics research group led by Deb Verhoeven demonstrates how empirical data from new digital sources can be used for research questions in film studies (cf. Verhoeven, 2016; Coat, Verhoeven, Arrowsmith & Zemaityte, 2017; Coate & Verhoeven, 2019).

New digital sources of data, often referred to as found (Japec et al., 2015), organic (Groves, 2011) or trace data (Golder & Macy, 2014; Stier et al., 2019) are sometimes criticized for not being suitable for research purposes due to poor data quality. Such general claims and skepticism, however, can be replaced by empirical investigation of the quality given a concrete research question. Organic data differ from traditional sources (often referred to as designed data) in the purpose and control over their creation (Groves, 2011). If we create a questionnaire for a survey or build an archive, we have a set of specific research questions in mind and actively oversee the data collection process. Organic data is being collected unobtrusively as a byproduct of other processes and not for a purpose of answering specific research questions. For example, an online program of a film festival is primarily created to announce films and not to serve as a sample of research data. Yet, we can also use these data to study programming of film festivals or the relationship between certain characteristics of films (e.g., production countries, genre, and gender composition of creative teams).

Given the above mentioned constrains of organic data, it is tenable that these sources have a number of data quality problems that need to be taken into account. Organic data are often incomplete, erroneous, and selective (Japec et al., 2015). For instance, films that are available on IMDb probably have systematic differences in certain characteristics from those not available on IMDb (e.g., smaller films or short films might be less represented on the platform). Although we cannot assure comprehensive data quality of these data sources, we can (empirically) evaluate their fitness for specific research questions. Moreover, we should acknowledge that no method of data collection is perfect, and we always have to be clear and transparent about its limitations and its data generation processes – routes and procedures by which data come into a database. Researchers and practitioners working with data are increasingly adopting strategies of data integration, since it allows the best tradeoff of strengths and weaknesses given specific research questions (Hill et al., 2019).

3. Sample and Data Sources Used in the Project

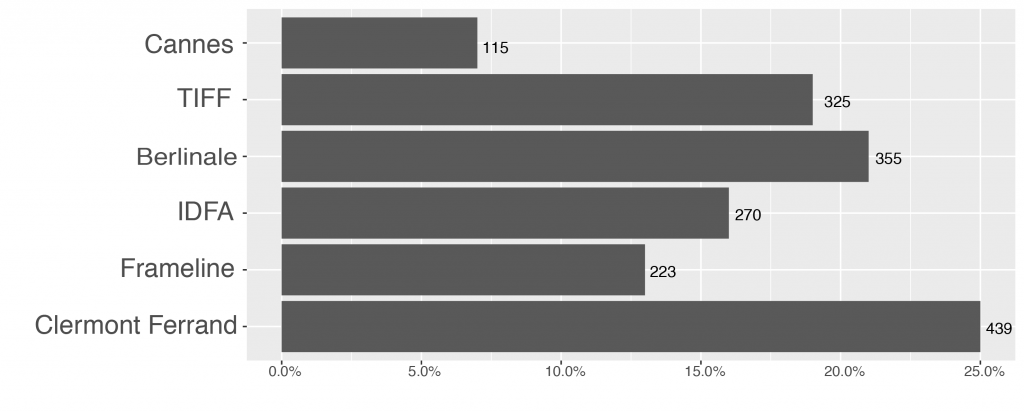

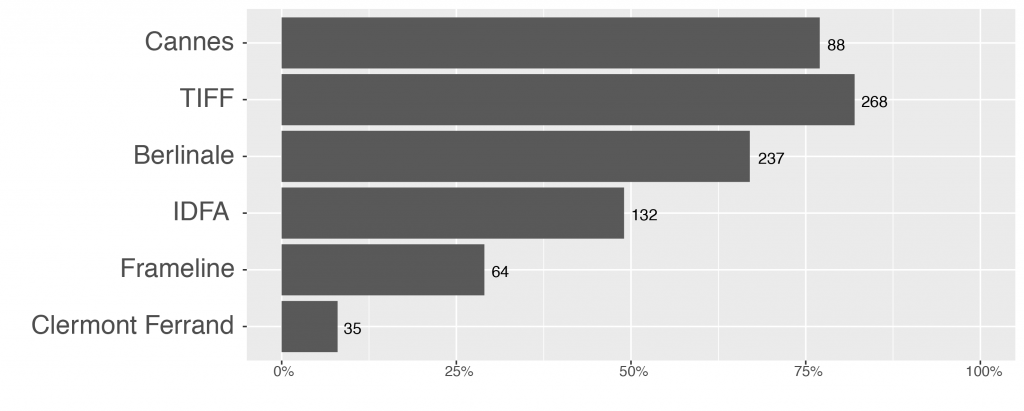

The sample of the project consists of films shown at six selected festivals in 2013. Due to collaboration with Kinomatics and since their 2012-2015 dataset was part of the original design, the year 2013 was chosen. The average duration of the festival run was expected to be around two-three years. The six festivals were chosen for their quality as premiere festivals, which act as launch pads for films who will circulate on the vast festival network. Their complete programs provide a wide diversity of films whose circulation patterns will represent the breadth of the festival network (cf. Loist, 2016, p. 52). Therefore, the first three festivals were chosen from the so-called A-festivals – festivals with international influence on the circuit and in the film industry – in different locations and placed at different times in the festival calendar: The Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale) in February, the Festival de Cannes in May and the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in September. In order to take into account films shown at parallel circuits (e.g. documentary film, short film and queer cinema) three further relevant festivals with a special focus were chosen: the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA), Clermont-Ferrand as a leading short film festival with a film market located in France, and Frameline as the oldest queer film festival based in San Francisco. As Figure 1 demonstrates, the sample is composed of 1.727 unique films. We differentiate here between 1.727 individual films and 1.806 film observations, because 67 films were shown at more than one of the six selected festivals. This already suggests the entanglement of the different circuits in our base sample.

Fig. 1 Percentage and count of unique films by festival, n=1.727. For the 67 films that were shown at more than one of the six festivals, the figure shows the first festival appearance.

To collect data on the festival run and its relation to other exhibition windows, we are using several data sources, which we describe below in more detail.

3.1 Festival Catalogues

The basis of data stems from the 2013 catalogues of the six festivals. With the exception of TIFF, all festival catalogues were available in a digital format. Since TIFF does not provide digital data from previous years, the data had to be collected from a printed catalog.

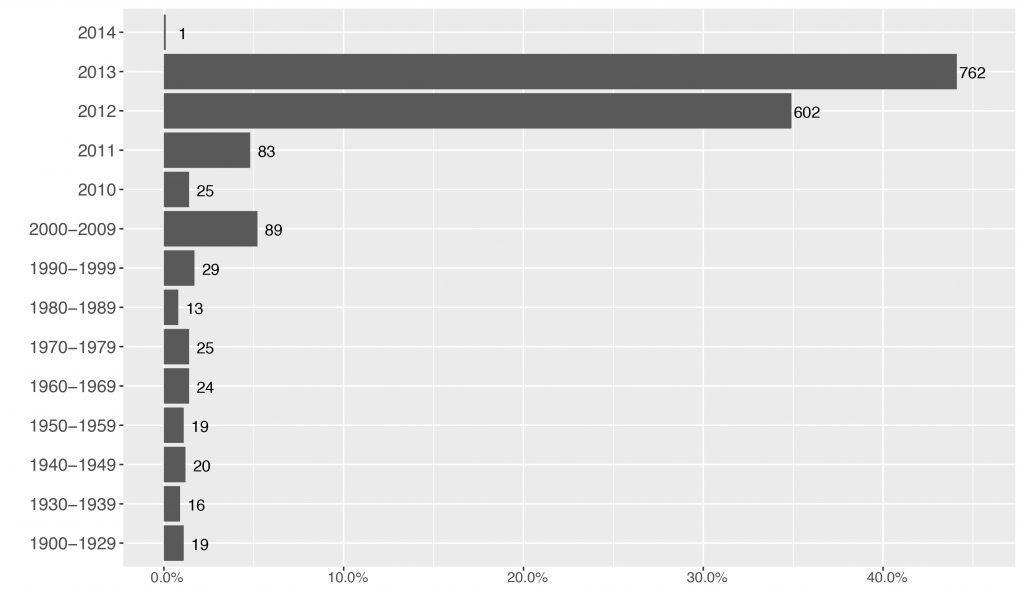

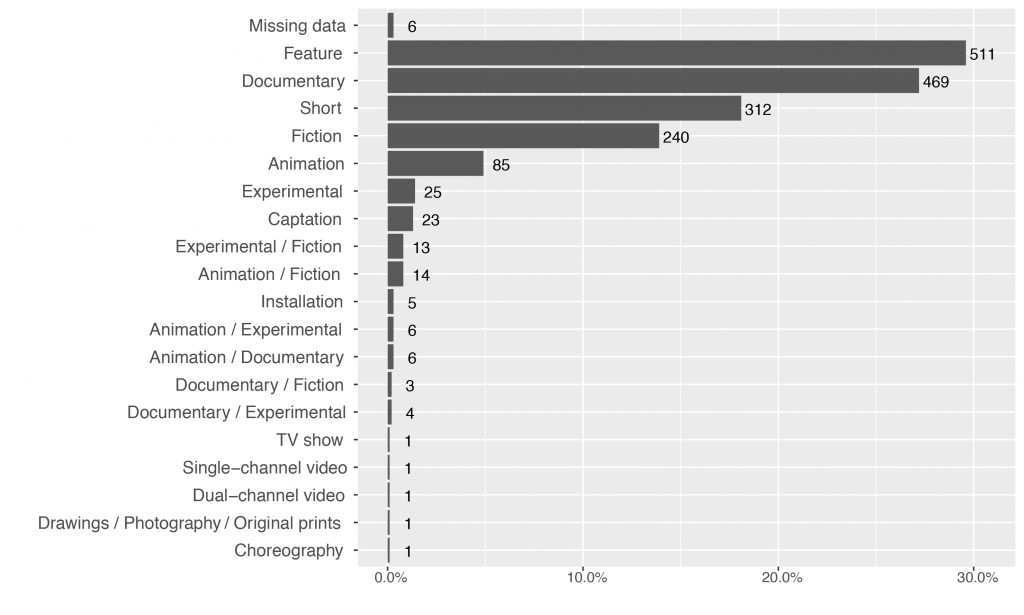

As Figures 2, 3, and 4 demonstrate, the resulting sample comprised 1.727 films of various genres from 102 countries produced between 1900 and 2014. Most films were produced in 2012 and 2013. Given the geographical location of the sample festivals, it is not surprising that the US and France are at the top of production countries. Genre is the only important variable with a notable share of missing data. In the festival catalogues, 312 films had only information on the film length (i.e., were characterized as short) without further specification of genre and six films had no genre labels. Genre for these films had to be completed via other sources such as key words available in the catalogues, manual research, and IMDb.

Fig. 2 Percentage and count of unique films by production year, n=1.727.

Fig. 3 Percentage of films produced by country, n=1.727. Films can have more than one country of production. To see country names and number of films for each country hover the mouse cursor over the graph.

Fig. 4 Percentage and count of unique films by genre as originally specified in the festival programs (before cleaning and re-coding), n=1.727.

3.2 Kinomatics Showtime Dataset

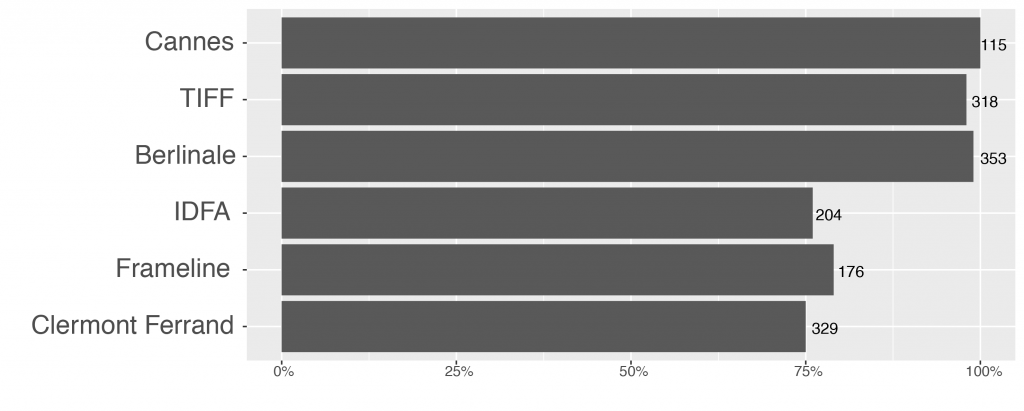

The corresponding piece of the data consists of the Kinomatics showtime dataset that contains information on classical theatrical release of films. For the field of film and distribution, Kinomatics is a pioneering project in leveraging Big Data for film studies. It works with a large dataset (over 338 million observations) purchased from a data broker company. The dataset contains prognostic data of almost 97.000 movies announced to be shown in cinemas in 48 countries in the thirty-month period between December 1, 2012 and May 31, 2015 (Verhoeven, 2016, p. 171). We were able to identify and link 48 percent of our films to the Kinomatics dataset. As Fig. 5 shows on average films screened at the A-level festivals (TIFF, Cannes, and Berlinale) were much more prevalent in the Kinomatics dataset than those from smaller specialized festivals. This is not surprising as IDFA, Frameline, and Clermont Ferrand have a smaller ratio of feature films tailoring to the traditional film release. 78 percent of films not found in the Kinomatics data are under 60 minutes.

Fig. 5 Percentage and count of films from the sample linked to the Kinomatics dataset by festival, n=1.727.

These data are very helpful for the detailed analysis of distribution in cinemas, as they contain location and showtime information on each screening of the film. Nevertheless, the data is limited to 48 countries. In addition, it includes only single observations of festival screenings, since festival screenings often take place in smaller cinemas that are usually not recorded digitally in commercial datasets on a large scale. Hence this data can only be used for theatrical distribution of films.

3.3 IMDb and Film Websites

IMDb is the most comprehensive, yet commercially operated (owned by Amazon) crowdsourcing-based film database. While the quality of the IMDb data makes it difficult to use it for historical research, it is an empirical question to what extent it can be used to collect data on festival and other types of distribution of films. The IMDb data contribution guidelines consider festivals to be a type of release (along with theatrical and TV releases). We were able to identify and link 87 percent of our films to the IMDb dataset. Similar to the linkage results in the case of the Kinomatics dataset, there is a clear difference between films from the A-level and more specialized festivals (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Percentage and count of films from the sample linked to IMDb data by festival, n=1.727.

IMDb also collects data on theatrical release, albeit only the first screening in each country. The latter allows us to corroborate these data with the Kinomatics dataset. 92 percent of the films identified on IMDb had some information about film festivals. Other variables with a good coverage include genre, names of the crew members, film length, production countries, and language. Problematic variables with a large share of missing data are budget (missing for 83 % of films), film websites (for 62 %), and box office (for 73 %).

Although the coverage of the IMDb data for our given sample is promising (87%), we cannot ignore questions of data quality. These questions need to be approached in an empirical way. Simply stating that IMDb data is generally of a bad quality does not suffice. Data collected in a smaller pilot study indicated that IMDb festival runs are only recorded in fragments, but they could be used for estimates of the festival run duration (in months). Another possible application of these data (that can be tested) could be to look at the festival distribution of big-budget films that tend to be distributed at more visible festivals such as for example A-level festivals. Such films and festivals are likely to have a better documentation on IMDb than smaller and less mainstream films. In this context IMDb could be a good alternative to traditional data collection methods such as surveys, as production and sales companies of more prominent films are much more difficult to approach.

4. Survey

In order to verify and supplement the incomplete festival runs listed on IMDb as well as collect data that is not available in any digital sources, we conducted a web-based survey among production companies and filmmakers related to our film sample. Experience from a pilot study has shown, that many producers or distributors collect data on the festival runs of their films. A survey is therefore potentially the best way to get an almost complete picture of the festival runs. Yet, the main problem of surveys (especially web-based surveys) is low response rates. The latter does not automatically affect the representativeness of a sample, but variable-specific nonresponse bias can occur and hence should be empirically examined. However, a moderate response rate can be helpful in analyzing the complete festival runs (at least exploratively and for a specific subgroup). While IMDb data can help us analyze a broad overall picture (with good film coverage) with a likely focus on visible and more prestigious festivals, the survey can provide us with insights into smaller films that are more likely to be distributed at smaller festivals.

The survey was sent out to 1.332 contacts that corresponded to 1.499 unique films. Films older than 1990 were excluded due to prevalent lack of contact details and low likelihood of response. 160 contacts were proven to be invalid. The survey ran from the end of May until the end of August 2019 and was sent with two reminders. The final sample resulted in 135 unique respondents providing information for 154 unique films (ca. 10 % response rate).

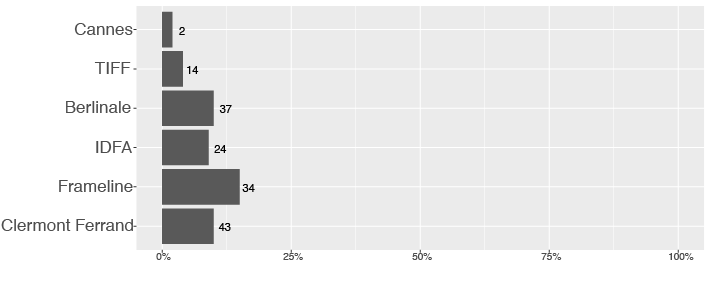

Unlike the IMDb and Kinomatics samples, the survey sample is dominated by films that screened at smaller festivals such as IDFA, Frameline and Clermont Ferrand (see Fig. 7). As expected, producers and filmmakers of films shown at Cannes and TIFF are very difficult to approach via a web survey.

Fig. 7 Percentage and count of film responses to the survey by festival, n=154.

5. Festival Library

In order to analyze film circulation on the festival network, we need data not only at the film level but also at the festival level. The festival level data are important in order to classify and cluster identified festivals according to their geographical, temporal, thematic and other characteristics. In addition, often data provided by digital sources or survey have missing information on month or/and location of the festival, which needs to be researched elsewhere. For such purposes we are currently collecting information on festivals listed in various sources including research communities, film institutions, as well as industry. While documenting the sources gives us an idea of the visibility of certain festivals, collecting data on their features such as, e.g. location, time, and topic can help us complete the missing data as well as cluster identified festivals at the final stage of analysis. Fig. 8 shows the geographical distribution of the 3.350 festivals currently listed in our database, which was collected from non-industry sources.

Fig. 8 Geographical distribution of festivals in the current festival library (data collection is ongoing). Colors correspond to percentages, n=3.350. To see country names and number of festivals for each country hover the mouse cursor over the graph.

6. Further Steps

To make sure we have a large enough sample size to take into consideration smaller subgroups of films (e.g., experimental films or films produced in certain countries) and to attempt sound statistical modelling, we are currently expanding the sample with additional 6 years of festival programs, so that the sample covers the range from 2011 to 2017. Although the study uses the computational turn in cinema studies, the focus is on the intersection of the above-mentioned methods with a reflective and critical perspective of film studies.

Notes

The project is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research under the number 01UL1710X.

We would like to acknowledge the help of Anne Marburger (Berlin International Film Festival) and Julien Westermann (Clermont-Ferrand Short Film Festival) in providing us with complimentary datasets for the extension of the study.

References

Coate, B., & Verhoeven, D. (2019). Show Me the Data! Uncovering the Evidence in Screen Media Industry Research. In L. Patti (Ed.), Writing about Screen Media (pp. 173–176). London, New York: Routledge.

Coate, B., Verhoeven, D., Arrowsmith, C., & Zemaityte, V. (2017). Feature Film Diversity on Australian Cinema Screens: Implications for Cultural Diversity Studies Using Big Data. In M. D. Ryan & B. Goldsmith (Eds.), Australian Screen in the 2000s (pp. 341–360). Cham: Springer International. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48299-6_16

De Valck, M. (2007). Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to Global Cinephilia. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Golder, S. A., & Macy, M. W. (2014). Digital Footprints: Opportunities and Challenges for Online Social Research. Annual Review of Sociology, 40(1), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043145

Groves, R. M. (2011). Three Eras of Survey Research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(5), 861–871. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfr057

Hill, C. A., Biemer, P., Buskirk, T., Callegaro, M., Córdova Cazar, A. L., Eck, A., . . . Sturgis, P. (2019). Exploring New Statistical Frontiers at the Intersection of Survey Science and Big Data: Convergence at ‘BigSurv18’. Survey Research Methods, 13(1), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.18148/srm/2019.v1i1.7467

Iordanova, D. (2009). The Film Festival Circuit. In D. Iordanova & R. Rhyne (Eds.), Film Festival Yearbook 1: The Festival Circuit (pp. 23–39). St. Andrews: St Andrews Film Studies.

Japec, L., Kreuter, F., Berg, M., Biemer, P., Decker, P., Lampe, C., . . . Usher, A. (2015). Big Data in Survey Research: AAPOR Task Force Report. Public Opinion Quarterly, 79(4), 839–880. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfv039

Loist, S. (2016). The Film Festival Circuit: Networks, Hierarchies, and Circulation. In M. de Valck, B. Kredell, & S. Loist (Eds.), Film Festivals: History, Theory, Method, Practice (pp. 49–64). London, New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637167-13

Mudhar, R., & Bailey, A. (2018, September 2). We Tracked Every Film that Played TIFF in 2017: Here’s What We Found. The Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/tiff/2018/09/02/we-tracked-every-film-that-played-tiff-in-2017-heres-what-we-found.html

Peirano, M. P. (2018). Film Mobilities and Circulation Practices in the Construction of Recent Chilean Cinema. In A. Kjaerulff, S. Kesselring, P. Peters, & K. Hannam (Eds.), Envisioning Networked Urban Mobilities: Art, Performances, Impacts (pp. 135–147). New York, NY, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Stier, S., Breuer, J., Siegers, P., & Thorson, K. (2019). Integrating Survey Data and Digital Trace Data: Key Issues in Developing an Emerging Field. Social Science Computer Review, 11, 089443931984366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439319843669

Sun, Y. (2015). Shaping Hong Kong Cinema’s New Icon: Milkyway Image at International Film Festivals. Transnational Cinemas, 6(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/20403526.2014.1002671

The Film Collaborative (2013, December 2). December 2013, #1: The Film Collaborative’s Festival Real Revenue Numbers and Comments regarding Transparency Trends. The Film Collaborative. Retrieved from http://www.thefilmcollaborative.org/_eblasts/collaborative_eblast_124.html

Vallejo, A. (2015). Documentary Filmmakers on the Circuit: A Festival Career from Czech Dream to Czech Peace. In C. Deprez & J. Pernin (Eds.), Post-1990 Documentary: Reconfiguring Independence (pp. 171–187). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Verhoeven, D. (2016). Show Me the History! Big Data Goes to the Movies. In C. R. Acland & E. Hoyt (Eds.), The Arclight Guidebook to Media History and the Digital Humanities (pp. 165–183). Sussex, England: REFRAME; Reframe Books in association with Project Arclight.